Australia, a land steeped in ancient Aboriginal culture and boasting a relatively recent but rich colonial history, faces a unique challenge: preserving its tangible past for future generations across a vast and often unforgiving landscape. From delicate Indigenous rock art weathered by millennia to the intricate details of colonial-era architecture susceptible to decay, the physical remnants of our heritage are constantly under threat. But a powerful alliance is emerging, a fusion of cutting-edge technology and profound respect for the past: 3D scanning and 3D printing.

This isn’t just about making fancy souvenirs. Across Australia, museums, historical societies, archaeological teams, and even community groups are increasingly turning to sophisticated 3D technologies to digitize, document, replicate, and ultimately safeguard invaluable pieces of Australian heritage. This innovative approach offers unprecedented opportunities for research, education, accessibility, and the long-term preservation of objects and sites that might otherwise be lost to time, natural disasters, or human impact.

Digitizing the Dust of Time: The Power of 3D Scanning

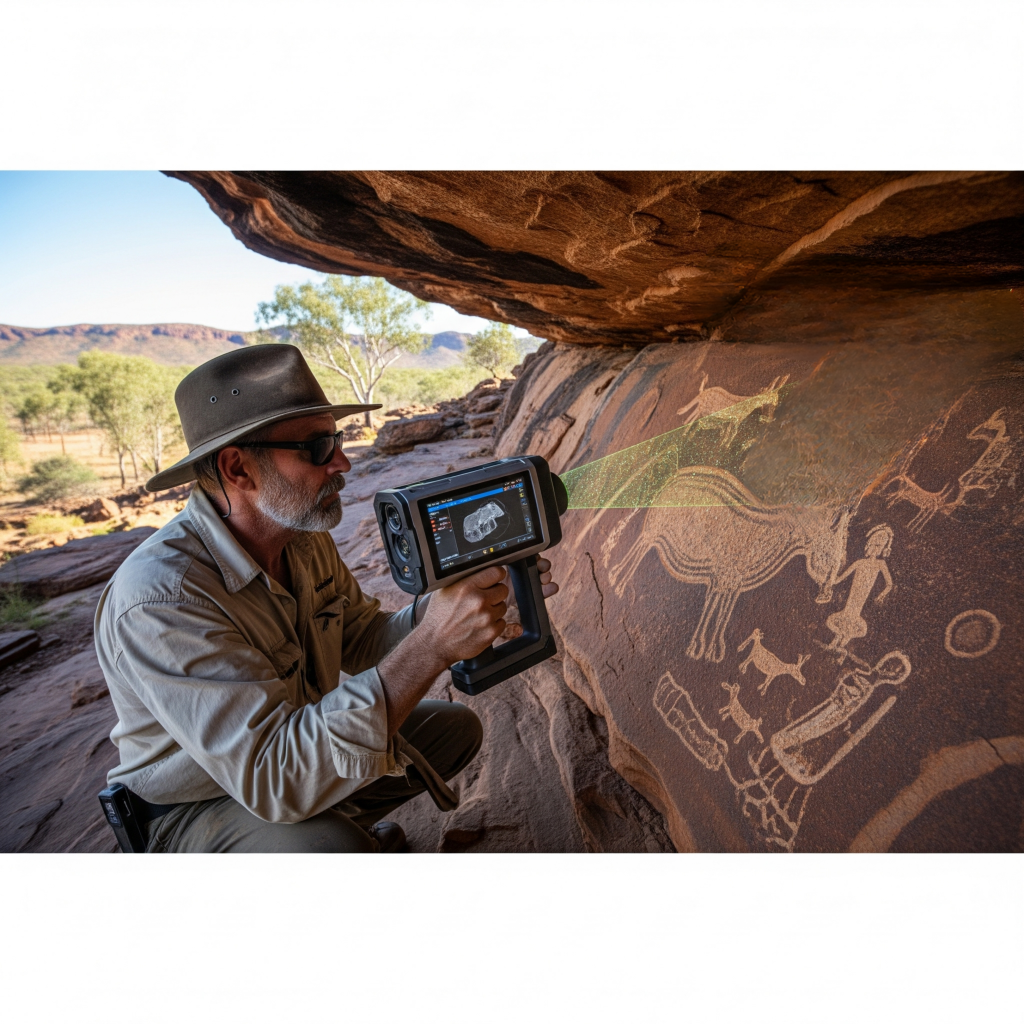

The first crucial step in this digital preservation journey is capturing the precise three-dimensional form of an object or site. This is where 3D scanning services come into play, offering a non-destructive and highly accurate method of creating digital twins of physical heritage. Various scanning technologies are employed, each with its own strengths:

- Structured Light Scanners: These project patterns of light onto an object and use cameras to capture the distortions, allowing for detailed surface reconstruction. They are ideal for smaller, intricate artifacts like tools, pottery shards, or even delicate biological specimens. Their precision allows for the capture of minute surface textures and details often invisible to the naked eye, creating a digital fidelity that was previously impossible. This technology is crucial for documenting fragile pieces that cannot withstand physical contact.

- Laser Scanners: These emit laser beams that bounce off the surface of an object or structure, measuring the distance and creating a “point cloud” – a collection of data points representing the object’s surface. Laser scanners are well-suited for larger objects, architectural elements, and even entire archaeological sites. Companies like Realserve, a leader in Australia, have successfully used 3D laser scanning, including LiDAR technology, to document vast heritage-listed sites in NSW, capturing every millimetre of the site’s external and internal structures. This provides an invaluable baseline for conservation, renovation, and even disaster recovery, as seen with the vital role 3D scans played in the reconstruction of Notre Dame Cathedral after the 2019 fire.

- Photogrammetry: This cost-effective method utilizes a series of overlapping photographs taken from different angles to generate a 3D model. It is particularly useful for large, immovable objects and landscapes, making it invaluable for documenting expansive rock art sites or historical buildings in situ. The Australian Museum, for instance, extensively uses photogrammetry to create 3D models of their diverse collections, from carved emu eggs to ancient Egyptian objects. This technique is also being developed for sites like the Baiame rock art cave in NSW, aiming to create an extremely realistic virtual tour that brings these sacred sites to a broader audience without risking damage to the fragile originals.

Imagine archaeologists meticulously scanning ancient Aboriginal rock carvings in the Northern Territory. The detailed digital models capture every groove, pigment variation, and weathering pattern, creating a permanent record that can be studied remotely by researchers worldwide, without the risk of further damage to the fragile original. This approach is invaluable in a country where many significant heritage sites are remote and vulnerable to environmental factors. Similarly, museums can digitally archive their entire collections, creating virtual repositories accessible to curators, researchers, and the public, regardless of geographical limitations. The Museums of History NSW (formerly Sydney Living Museums) have embarked on a significant project to capture 3D scans of their properties, creating a complete digital record of their sites and collections for conservation and interpretation. This digital twin can serve as a critical reference point for monitoring decay, planning restoration, or even rebuilding if a site is ever severely damaged.

From Pixels to Polymers: The Versatility of 3D Printing

Once a heritage object or site has been accurately digitized, the possibilities unlocked by 3D printing services are truly transformative. These digital blueprints can be brought back into the physical realm through additive manufacturing, layer by layer, using a variety of materials. The applications for this are vast and constantly evolving:

- Creating Exact Replicas for Research and Education: Researchers can handle and study precise replicas of fragile or hazardous artifacts without risking damage to the originals. This is particularly vital for delicate archaeological finds or highly sensitive cultural objects that are too precious to be regularly handled. Students can engage with tangible representations of history, fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation than simply viewing images. Imagine a classroom in regional Queensland holding a 3D printed replica of a colonial-era tool unearthed in Western Australia, allowing for tactile learning experiences that would be impossible with the original. This direct, hands-on interaction can significantly enhance learning and engagement, especially for younger learners, making history come alive. Museums are increasingly using these replicas for educational outreach programs, extending their reach far beyond their physical walls and fostering a new generation of heritage enthusiasts.

- Enhancing Museum Exhibitions and Accessibility: 3D printed replicas can be incorporated into museum displays, allowing visually impaired visitors to experience the shape and texture of historical objects, breaking down barriers to engagement. The “Museum of Touch” project in Australia specifically leverages 3D printing to create tactile models that make museums inclusive for all, demonstrating how technology can promote empathy and understanding through sensory experiences. Damaged or incomplete artifacts can be partially reconstructed, offering a more complete understanding of their original form. For institutions with limited space, 3D printed collections can be rotated or even sent to outreach programs in remote communities, democratizing access to Australia’s heritage. The Maritime Museum of Tasmania, for instance, successfully used 3D printing to create a replica 19th-century ornate gilt frame for an oil painting, showcasing a pioneering use of the technology in Australian conservation and demonstrating how it can fill gaps in historical objects. Museums of History NSW are also using 3D printed facsimiles for exhibition, such as a replica of the 1788 headstone of First Fleet sailor George Graves, allowing the original to be safely preserved while providing an accurate physical representation for visitors.

- Conservation and Reconstruction: In cases where original architectural elements are severely damaged or missing, 3D printing can be used to create accurate replacements. This technology allows for the faithful restoration of historical buildings, ensuring their longevity and preserving their aesthetic and cultural significance. For instance, intricate decorative features on a Victorian-era building in Melbourne could be meticulously scanned, digitally repaired, and then 3D printed for seamless integration into the original structure. For large-scale reconstruction, technologies like concrete 3D printing are being explored, offering the ability to reproduce lost or damaged elements without needing traditional skilled artisans, optimising material consumption and execution time. This capability is revolutionary for preserving the integrity of historical structures in the face of natural decay or unforeseen damage, ensuring that Australia’s built heritage stands for centuries to come.

- Remote Study and Collaboration: High-resolution 3D models can be easily shared across the globe, facilitating collaboration between researchers and institutions regardless of their physical location. An archaeologist in Perth could virtually examine a fossil discovered in outback NSW in intricate detail, collaborating with paleontologists in Europe or North America. This global accessibility extends the reach and impact of Australian heritage research significantly, fostering international partnerships and accelerating discovery. Furthermore, these digital assets can form the basis of virtual museums, online archives, and interactive educational platforms, making Australian heritage accessible to anyone with an internet connection. The Australian National Maritime Museum, for example, is home to the “Barangaroo Boat,” Australia’s oldest colonial boat, which was meticulously 3D scanned and documented by the Silentworld Foundation, allowing for its reconstruction and display. This project highlights the power of 3D technology in bringing submerged history to the surface and to a global audience.

Australian Initiatives Leading the Way

Across Australia, innovative projects are already demonstrating the power of this technological synergy. The Australian Museum, a venerable institution, pioneers the use of 3D scanning and printing to create accessible museum experiences and document their vast collections, ensuring these treasures are preserved and widely shareable. Their work contributes to initiatives like Ozboneviz, creating open-access 3D imagery of biodiversity specimens, which has direct parallels for cultural heritage. The Silentworld Foundation, an Australian non-profit focused on marine archaeology, successfully used Artec 3D scanners to digitise Australia’s oldest colonial boat, the “Barangaroo Boat,” enabling its detailed reconstruction and display at the Australian National Maritime Museum. This allowed for meticulous documentation of a fragile find that was destined for deterioration.

Beyond major institutions, initiatives like the collaboration between the National Trust SA and Makers Empire are bringing 3D printing into schools, allowing students to learn about local history by designing and 3D printing models of heritage buildings in their area. This not only fosters an appreciation for local heritage but also equips younger generations with valuable digital design and manufacturing skills, creating a pipeline of future heritage innovators. The Perth Observatory Challenge, another Makers Empire initiative, engages West Australian primary school students in learning about the observatory’s heritage through 3D design and printing, proving the educational power of this technology in engaging young minds.

The potential extends even further. Imagine 3D printed models of significant historical landscapes used in tourism to provide a tangible context for visitors, allowing them to grasp the scale and features of a site more intuitively. Consider the creation of personalized 3D printed learning tools for Indigenous communities to connect with their cultural heritage in new and engaging ways, ensuring that traditional knowledge is passed down through modern mediums. The possibilities are as vast and diverse as Australia itself.

Ethical Considerations and the Path Forward

While the potential of 3D scanning and printing for heritage preservation in Australia is immense, there are crucial challenges and ethical considerations that must be diligently addressed to ensure responsible and respectful implementation.

- Cost and Accessibility: The cost of high-end scanning equipment and professional 3D printing services can be a barrier for smaller institutions, regional museums, and community groups. Democratizing access to these technologies is vital to ensure that heritage efforts are not limited to well-resourced institutions in major cities. Strategies could include mobile scanning units, shared equipment pools, or government subsidies for regional heritage projects, as well as developing more affordable, user-friendly scanning and printing solutions.

- Expertise and Training: A skilled workforce is required to operate the sophisticated equipment, process the vast amounts of data, and understand the nuances of heritage conservation. Investment in training and education programs for heritage professionals, archaeologists, and museum staff is essential to build this capacity within Australia. Partnerships between universities, TAFE colleges, and technology providers will be crucial to bridge this knowledge gap.

- Authenticity and Context: While replicas offer incredible benefits, it’s crucial to distinguish them clearly from the original artifacts. Discussions around “authenticity” and how replicas are presented in exhibitions and educational settings are ongoing within the heritage sector. Transparency about the creation process and the purpose of the replica is key to maintaining trust and respect for the original object’s history and ensuring that the public understands the difference between an original and a reproduction.

- Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP): Perhaps the most significant ethical consideration in an Australian context relates to the digitization and replication of Indigenous heritage. There is a strong emphasis on ensuring that 3D printing services and scanning projects involving Indigenous cultural materials are undertaken with the explicit Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) of relevant Traditional Owners and communities. Issues of ownership, access, control, and respectful representation are paramount. Projects must adhere to principles like Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics (CARE principles) and Indigenous Data Sovereignty, ensuring that Indigenous communities retain authority over their heritage data and its use. This often means co-designing projects, ensuring Indigenous voices guide the process from inception to dissemination. The potential for commercialisation of Indigenous cultural heritage through 3D printing also requires careful ethical oversight and benefit-sharing agreements, preventing exploitation and promoting equitable partnerships.

- Long-term Digital Preservation: Creating digital twins is only the first step. Ensuring the long-term integrity and accessibility of these digital files (3D models, point clouds, associated metadata) requires robust digital preservation strategies and infrastructure. Data formats must be open and sustainable, and secure storage solutions are needed to protect these invaluable digital assets from obsolescence or loss. Australia’s cultural institutions need to invest in digital archiving capabilities to match their physical preservation efforts.

However, as the technology becomes more accessible and affordable, and as interdisciplinary collaborations between heritage professionals and technology experts grow, these challenges can be overcome. Government funding initiatives, community grants, and the increasing availability of skilled 3D printing services across Australia will play a vital role in democratizing access to these powerful tools. Continuous dialogue with Indigenous communities is essential to develop best practices that are respectful, collaborative, and empowering, ensuring that technology serves heritage rather than dominates it.

Join the Conversation: Preserving Our Past, Shaping Our Future

The integration of 3D scanning and printing into the realm of Australian heritage preservation marks a significant step towards safeguarding our past for the future. It offers new avenues for research, education, accessibility, and the sheer wonder of connecting with tangible links to those who came before us.

We invite you to share your thoughts and experiences on this exciting intersection of technology and history.

- What other unique applications of 3D scanning and printing in Australian heritage can you envision?

- How can we ensure these technologies are accessible to all communities and heritage organizations across Australia, particularly those in regional and remote areas?

- What ethical considerations do you believe are most important to address as we increasingly rely on digital reproductions of our cultural heritage, especially concerning Indigenous cultural heritage?

Leave your comments below and let’s continue this important conversation. Together, we can harness the power of innovation to ensure that the stories etched in stone, timber, and artifact continue to resonate for generations to come.

Are you interested in exploring how 3D scanning and printing can benefit your heritage project or organization? Contact NE Solution today to discuss our comprehensive 3D printing services and discover how we can help you preserve Australia’s unique past for the future.